Five Important Lessons on Pursuing Energy Justice From The “Decolonizing Energy” Conference

At Georgetown University in Qatar’s eleventh Hiwaraat conference, Decolonizing Energy: The Past, Present, and Future of Energy Justice, scholars and creatives offered key insights into the future of energy justice. Conference co-organizer Dr. Trish Kahle framed the weekend as both critique and invitation: “There is a dual need for action to end colonial energy violence alongside a reimagination of energy systems not premised on exploitation, extractivism, and theft. We invite you to imagine with us worlds and humanities beyond extractivism.”

Here are five takeaways from the timely symposium:

1. Colonial legacies still shape global energy systems today.

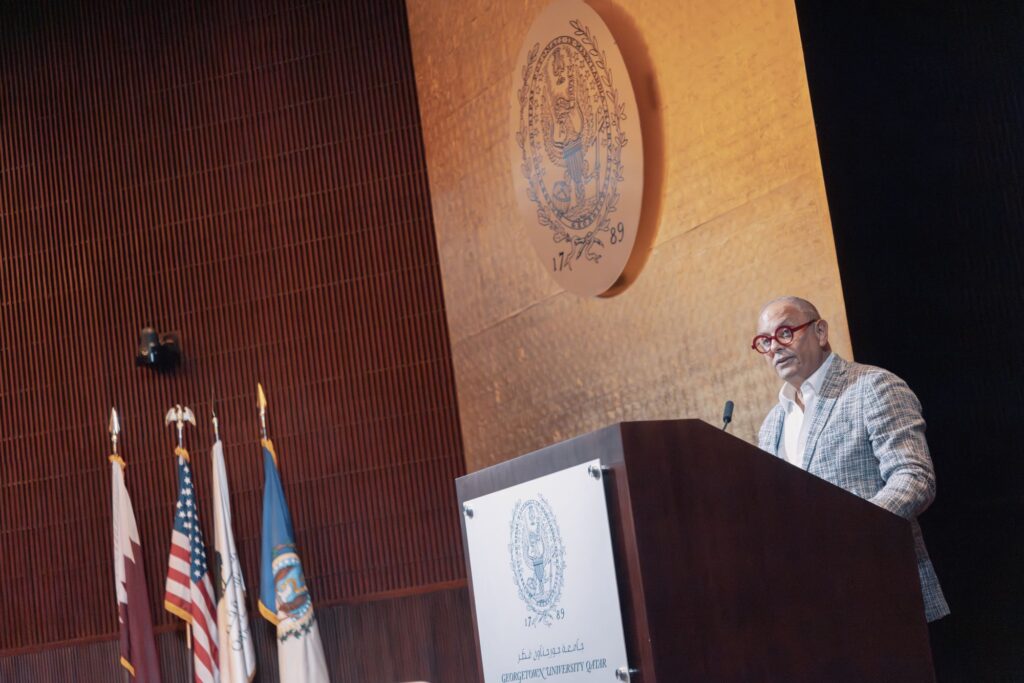

Dean Safwan Masri opened with a reminder of how deeply colonial hierarchies persist: “For decades, predatory models of development have been exported wholesale to the Global South, creating a narrative of progress that omits those who pay the price for its products.” Speakers traced these patterns through contemporary case studies. Dr. Hannah Appel of UCLA illustrated this through the intersection of Jim Crow segregation and U.S. colonialism on Navy ships: “Today, that Filipino men are one in three workers at sea shows how labor markets in the transnational oil and gas industry are completely caught up in colonial histories.”

Dean Safwan Masri

Dr. Hannah Appel

2. The stories we tell about energy are flawed.

Dr. Jennifer Wenzel of Columbia University described how extractive systems replicate themselves across nations, along with the false narratives they tell about progress. “When we think about energy transition, it is too often a substitution of fuels—but it’s not a replacement, it’s a proliferation of masters and fuels.” Dr. Ala’a Shehabi of UCL went further: “We reject the idea of energy transition in the first place—it’s an energy expansion.”

Dr. Jennifer Wenzel

Dr. Ala’a Shehabi

3. Human and environmental visibility—and invisibility—are political.

The global energy system depends as much on what is hidden as on what is seen. Dr. Wenzel noted, “What you see depends on where you stand. For those at sites of extraction, it is hypervisible.” Dr. Appel added that “Making things invisible is a political project.” She detailed how the human and environmental costs of oil in Nigeria were made visible “thanks in large part to poets and artists,” and described how oil companies in Equatorial Guinea have chosen to drill offshore in order to render their activities less visible.

4. Decolonizing energy requires new tools and perspectives.

Speakers called for interdisciplinary and participatory research methods. Dr. Elizabeth DeLoughrey of UCLA emphasized upending dominant narratives through storytelling, urging more engagement with Global South literature and poetry that “tell a different story.”

Dr. Gökçe Günel

Echoing Dr. Appel’s example of contemporary worker composition on boats, Dr. Gökçe Günel of Rice University shared how tracing stories about the workers and infrastructure behind energy “sheds light on how colonial relations manifest in the contemporary era.”

Examples of effective research methodologies included Dr. Dana Abi-Ghanem of the Ebla Research Collective and Arab Reform Initiative, and Dr. Muzna Al-Masri of UCL’s participatory Community Building project in Beirut, which employed residents to identify energy inequities on site. Project participant Mostafa Soueid reflected on the methodology, saying: “There is less distance between the researcher and what is being researched—they center the participants’ voices.”

Dr. Dana Abi-Ghanem

Dr. Muzna Al-Masri

Dr. Shehabi summarized her humanity-forward approach to researching oil companies in Bahrain: “By inverting your research questions ontologically, you recenter the indigenous scale.”

5. Energy justice requires activating our humanity.

Cameroonian maker Pascale Marthine Tayou, who uses found objects in his pieces, challenged both geo-political structures and personal complacency during his keynote. “I don’t recycle things; I recycle mentality. It is our responsibility to change.” He urged citizens of the Global South to claim their agency: “You from the South, who are consuming things from the North, need to find a way to use your own language and voice to put a stop to it.”

Maker Pascale Marthine Tayou

Author Imbolo Mbue

The conference’s final panel featured GU-Q Writer-in-Residence Kamila Shamsie in conversation with award-winning author Imbolo Mbue. Conference co-organizer Dr. Victoria Googasian noted that Mbue’s novel How Beautiful We Were provided an early inspiration for the conference, because “it turns an unsettling eye to the way the imperial commitment to oil extractivism rebounds across generations, linking past and future.”

In her remarks, Mbue reflected: “I grew up in Limbe, Cameroon, which had the country’s only oil refinery.” Despite the injustices she witnessed, she underscored how empathy fosters understanding. “I had to separate from my own anger and paint both sides with equal complexity,” she shared. She hopes her novel inspires action in the youth of today “who show evidence of being braver and more aware” than her own generation. “My role was just to tell the story, and maybe the next person will carry it on,” she said.

At the conclusion of the conference, Dr. Firat Oruc offered a guiding vision beyond policy or advocacy for those seeking to carry forward the work of energy justice: “Energetic decoloniality is not merely a political project. It asks us to cultivate other ways of being in the world—to shift from extraction to relation, from possession to participation, and from domination to reciprocity.”