A Kashmiri Rugman: Story of Riyaz

August 6, 2021

Uday Chandra and Taha Kaleem

In our global village, everyday acts of consumption define who we are (or not), where we belong (or don’t belong), and the sociocultural worlds we actively co-create with others (or in opposition to others). Consumption IS politics: it blends cosmopolitanism and localism, encompasses migration and citizenship, and takes us through journeys into myriad pasts of colonial conquest, long-lost jewels, and the postmodern politics of heritage.

This series of posts, titled “Consuming Doha,” seeks to take readers on a voyage of discovery. We visit old favorites and places unseen in the city, telling the stories behind each of them and the rich associations they conjure up for us. We write about food, but also the people that feed and serve us. We talk about places, but the invisible social dynamics that make them possible at all. Above all, we stay clear of the posh and the prim, the bougie and brash, the fine and not-so-fining dining options in a city of and by migrants.

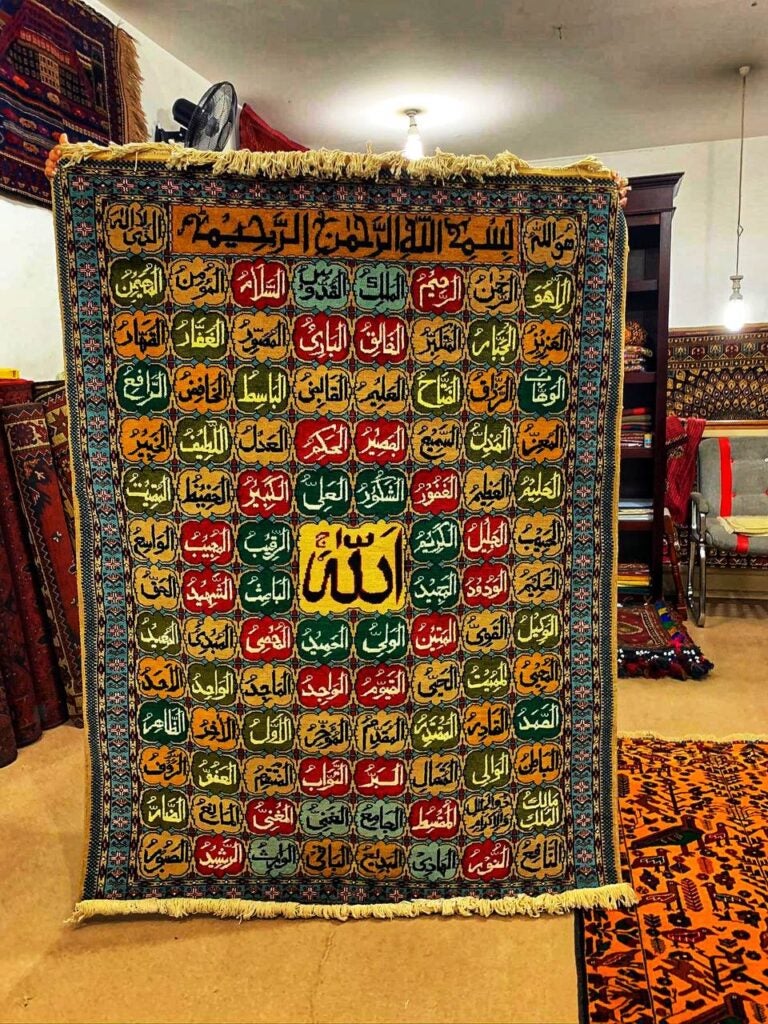

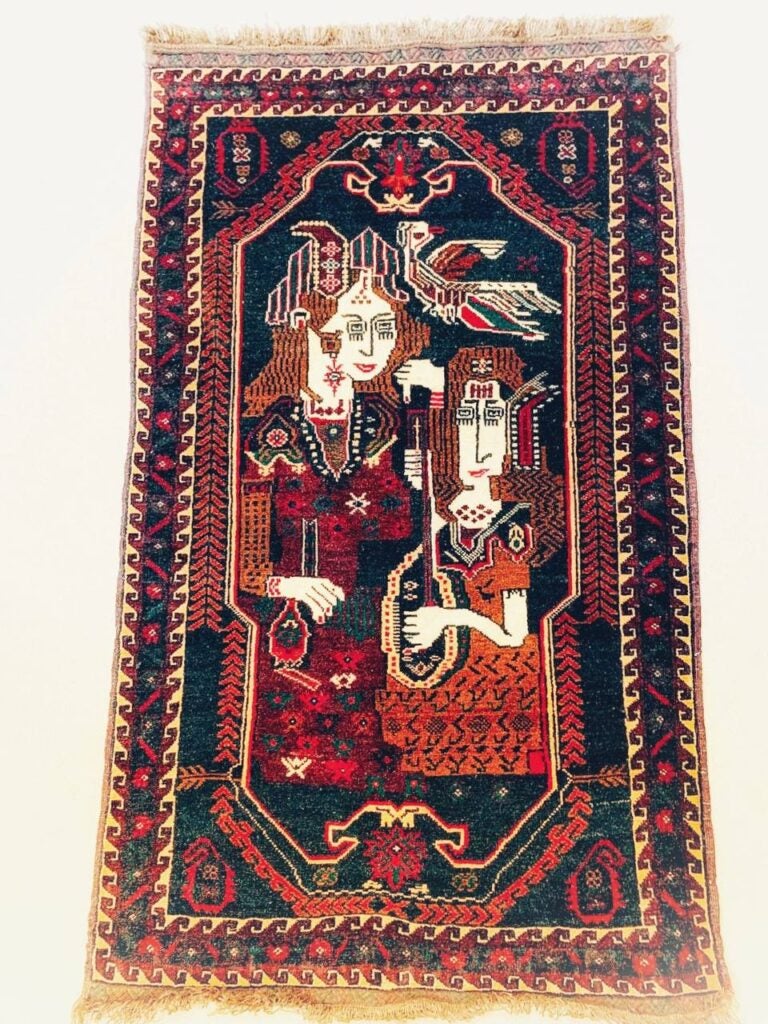

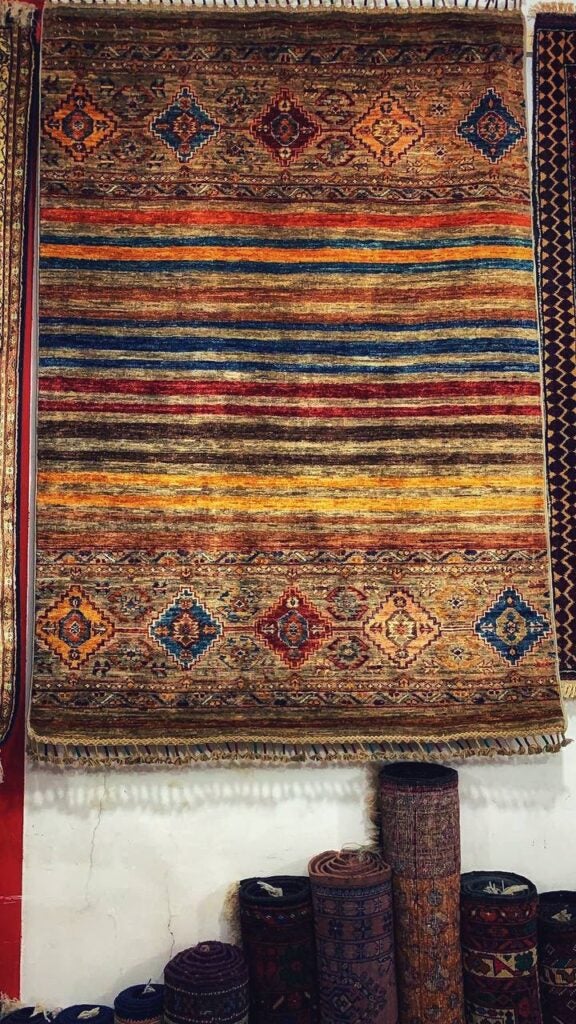

Every carpet tells a story, observes Riyaz Bhatt, Doha’s famous “rug man.” Some depict AK-47s and Kalashnikovs. Others portray hunters on horseback and damsels in distress. War-torn Afghanistan and Kashmir are renowned today for their intricately-crafted carpets.

The history of the craft, however, goes back arguably two and a half millennia to the vast Inner Asian sphere of steppe nomadic mobilities from Anatolia in the west to Siberia in the east. Felt carpets made of compressed wool, created by accident or design, might have been the norm in antiquity, but we are more familiar today with the warp and weft of weaving wool or silk yarn.

Riyaz has a remarkable story of his own. He hails from a family of Kashmiri carpet weavers. But, as a teenager, he realized that he could not weave carpets like his father. He was, nonetheless, fascinated by carpets. In the 1980s, when the Kashmir valley erupted in an armed insurgency against Indian occupation, young men of Riyaz’s generation crossed the border into Pakistan to train in camps. Riyaz also left home and went to Islamabad to join his uncle’s carpet business.

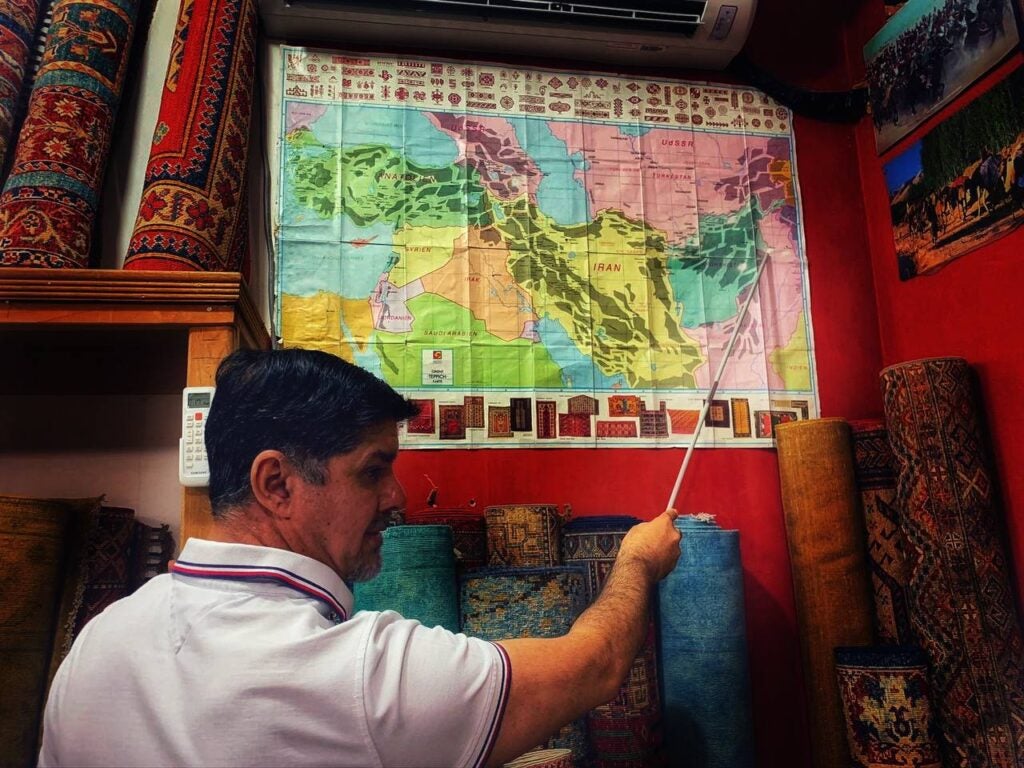

As he learned the finer points of the trade, Riyaz studied scores of designs and marveled at the sophistication of the weavers. Who were they? How did they create these incredibly detailed designs? What inspired them? To answer these questions, he travelled at considerable personal risk to the highlands of Afghanistan to find the communities that passed on ancestral looms and weaving techniques as well as folklore and songs from generation to generation.

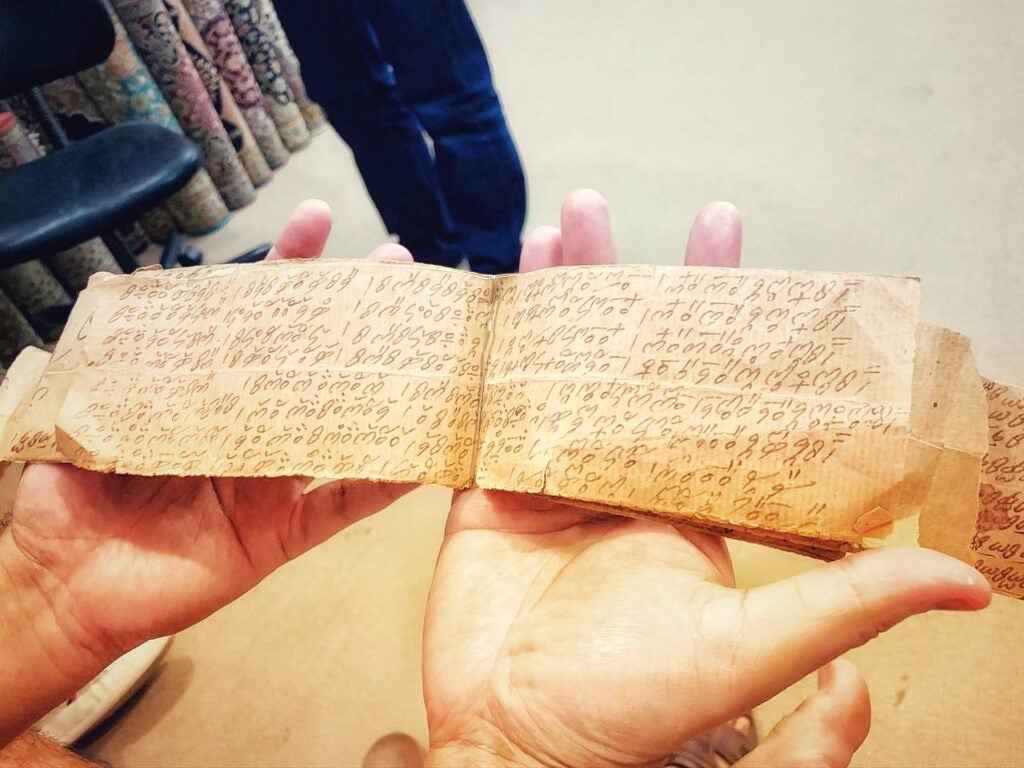

Each carpet is a song, numbers and letters standing for musical notes as much as carpet knots. At the same time, each song is a prayer unto the divine and the lived tradition of marginalized groups fighting for survival amidst the latest iteration of the Great Game in Inner Asia. To speak to the women who weave and sing in these groups was itself a challenge for Riyaz. Yet he persevered and persuaded the community elders to permit him to learn about the creative genius of their womenfolk.

In 1999, with the aid of a Qatari kafeel or patron, Riyaz launched Doha’s best-loved rug store. Located on the same road as the magnificent Mirqab Mall, the Rugman of Al Sadd is where the Silk Roads meet the Indian Ocean. Kashmiri shawls and stoles and handicrafts made of walnut wood and papier mache occupy the ground floor of the store. These objects have long been prized by Gulf sheikhs. Embroidered Kashmiri shawls continue to adorn winter thawbs worn by Qatari men today.

On the upper floor, visitors are greeted by hundreds of carpets of varying sizes and shapes, each with a story that Riyaz narrates with panache. Few know carpets as well as Riyaz. He regularly travels back home to Kashmir, neighboring Pakistan and Afghanistan, and farther afield to Iran, Turkey, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan to pick each carpet that lines his shop. He can tell you the exact number of knots per square inch or the circumstances that led to a curious quirk in a carpet’s design.

It is useful to remember, as Riyaz reminds us, that each carpet is handmade and its aesthetic beauty is tied inextricably to its imperfections. This is a craft that is seemingly impervious to the mechanical impulses of modern life

Some carpets narrate ballads of ill-fated lovers and nomadic warriors on campaign against their rivals. Others explore the hidden geometry of rosettes or serve as horse saddlecloths. These handwoven carpets of silk and wool often carry the totemic markers of the mobile communities that craft them. Now as before, these are prestige goods, owned and gifted by men and women of status.

The Qatari citizens and expatriates who flock to the Rugman are the latest in a long line of wealthy individuals and households who invest in this peculiar form of luxury consumption. When Riyaz came to Doha, he had no idea he could run a successful migrant business for over two decades. He sees himself as a key link between his well-to-do patrons and the carpet weavers he visits. Those who buy these carpets are compelled to recognize the oft-overlooked aesthetic dimension of consumption. Carpets are not mere stores of value. To own a Kashan or Isfahan carpet is a mark of aesthetic judgment on the part of its owner.

Education City holds a special place for Riyaz. Faculty and administrators at these branch campuses are regular visitors at the Rugman. A former dean at one of these campuses, he says, bought as many as 120 carpets to adorn her post-retirement home in the US. Loyal customers bring visiting family and friends to Doha, who wish to take back and show off a Persian rug halfway across the world. The most affordable rugs cost around 10,000 riyals (approx. 3,000 US dollars), but be ready to pay at least twice that amount for the best in the business.

The consumption of a luxury commodity is a semiotic act in which the identity of the consumer and the identity of the object are conjoined to each other. Those who purchase the Rugman’s carpets become, willy nilly, the consumers of Riyaz’s stories too. These are stories of warp and weft, but also songs and prayers of nomadic women whose livelihoods depend on men such as Riyaz.

In this sense, Doha is much more than a meeting place for buyers and sellers of luxury goods. It is also where people find refuge after leaving home and where they fuse older traditions with newer ways of living. Betwixt and between the diverse worlds of the city’s migrants, the Rugman brings together the myriad meanings of consumption.

“The posts and comments on this blog are the views and opinions of the author(s). Posts and comments are the sole responsibility of the authors. They are not approved or endorsed by Georgetown University in Qatar, or Georgetown University and do not represent the views, opinions or policies of the University.”